about

Beyond the aria

I’m a Polish performer working at the intersection of opera, music, theatre, and the experimental stage.

I have performed under grand chandeliers and in bare rooms with nothing but a chair and a lightbulb. I feel equally at home in both worlds — each feeds my imagination in a different way. My path leads through different stages, cities, and languages, but I am always searching for the same thing: the moment when music, words, and presence meet to create something unrepeatable.

MY STORY

Then came the injury — a fractured vertebra that ended my sporting plans overnight.

Music had been in my life for years, though mostly in the background. I taught myself guitar, sang in a schola, and in my final year of school began formal vocal training. After graduation, I moved to Wrocław to study geology and, at the same time, enrolled in a music school. But geology quickly proved to be a full‑time life — fieldwork, labs, and a huge workload. I had to set music aside.

For five years, I didn’t sing at all.

Then, at 25, I returned to my former professor Bogdan Makal “just for a hobby” lesson. Instead, I heard: “If you want to grow, you have to go back to studying.” With his help, I was accepted into the Academy of Music. I caught up on theory, but my focus shifted more and more to the stage — first in productions directed by Roberto Skolmowski, then at Song of the Goat Theatre with artists from all over the world. Today, I work in both opera and theatre. Returning to music was the best decision I’ve ever made. I step onto the stage as if it were my last time — because that’s the only way it’s worth being there.

full bio

He studied at the Karol Lipiński Academy of Music in Wrocław with Professor Bogdan Makal and at the Hochschule für Musik Carl Maria von Weber in Dresden with Professor Edward Randall. Before embarking on formal music studies, Bońkowski graduated in geology and petroleum engineering and worked professionally in the field. At the outset of the career, a fruitful collaboration with director Roberto Skolmowski led to acclaimed performances in revivals of rarely staged operettas and vaudevilles by Stanisław Moniuszko. These productions contributed to the rediscovery of a lesser‑known part of the composer’s legacy and showcased versatility across both operatic and theatrical repertoire.

Over the years, Bońkowski has shaped a career marked by stylistic breadth and dramatic range, portraying — among others — Zuniga in Bizet’s Carmen, Uberto in Pergolesi’s La serva padrona, Polyphemus in Händel’s Acis and Galatea, Magician Celio in Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, and Fotis the Priest in Martinů’s The Greek Passion. He has appeared in both ensemble and leading parts, often in productions demanding strong acting skills alongside vocal mastery. Collaborations with conductors such as Sylvain Cambreling, Giancarlo Guerrero, Giuseppe Finzi, and Valerio Galli have brought him to projects of high artistic profile, while masterclasses with Francesco Bottigliero, Sylvain Cambreling, Riccardo Mascia, Eytan Pessen, Matthias Rexroth, and Wolfgang Schöne have further refined his craft.

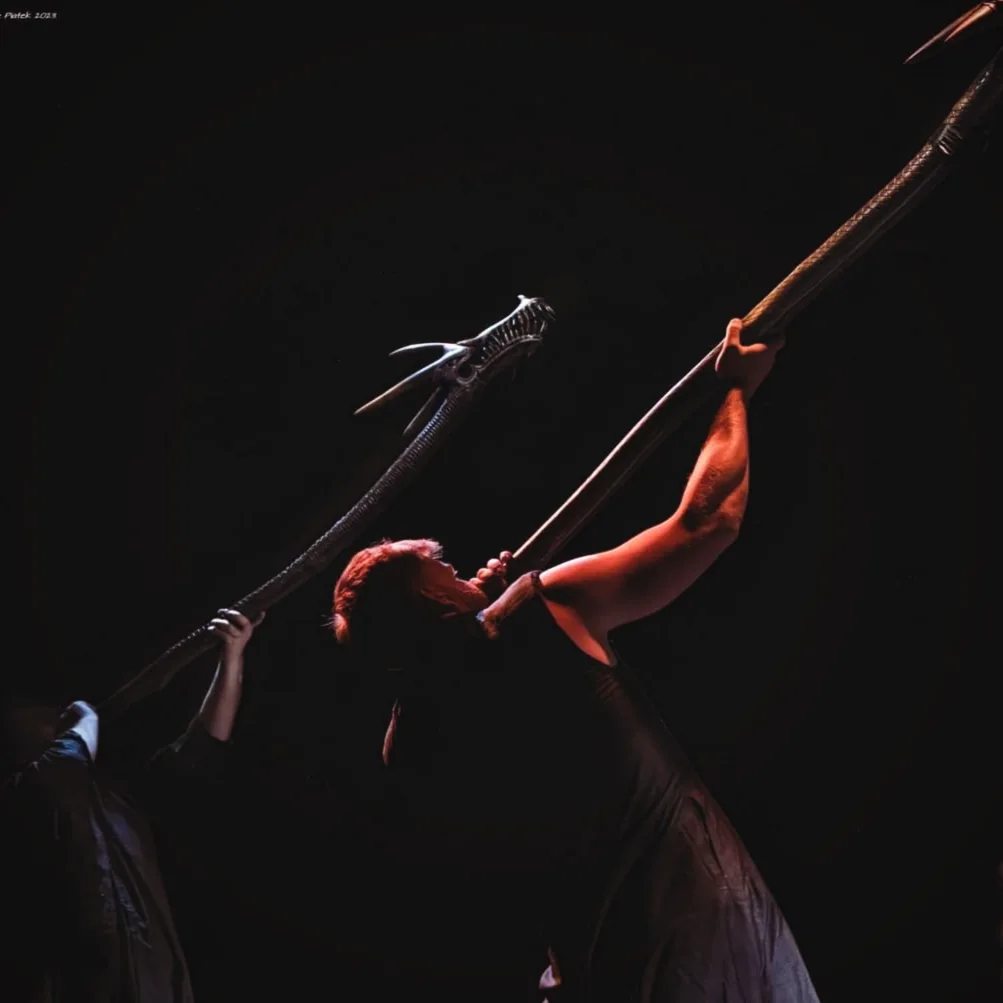

Alongside operatic commitments, Bońkowski is a permanent member of the acclaimed Song of the Goat Theatre – one of Europe’s most innovative and internationally recognised theatre companies. Productions such as Hamlet – A Commentary, Songs of Lear, Return to the Voice, Antigone, Warrior, Andronicus Synecdoche and Cassandra’s Report have been presented at prestigious venues and festivals including Shakespeare’s Globe in London, the Israel Festival in Jerusalem, FITS Festival in Sibiu, Hamletscenen in Helsingør, Beijing Tianqiao Performing Arts Center, the Great Theater of China in Shanghai, Shanghai Oriental Arts Center, Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley, the Gdańsk Shakespeare Festival, and the Warsaw Theatre Meetings.

On the concert platform, Bońkowski has performed Bach’s Weihnachtsoratorium, Handel’s Messiah, Beethoven’s Mass in C major, Rafał Augustyn’s Descensus Christi, and Żebrowski’s Magnificat, as well as recital programmes featuring Moniuszko’s songs, Dvořák’s Biblical Songs, and Shostakovich’s Spanish Songs. He also collaborates with the Ars Augusta association on special projects, including productions of Das Wichtelchen and Pergolesi’s La serva padrona, as well as recordings of works by Robert Kahn.

STAGE TRUTH

The Beginning of the Journey

In 2018, while still a second-year opera student at the Academy of Music, I found myself — quite unexpectedly — at the Song of the Goat Theatre in Wrocław, Poland. I wasn’t looking for theatre; theatre found me. I was inexperienced, yet surrounded by artists of remarkable skill and diverse creative paths. Sharing the stage with them, I learned at a pace I had never known before. It was there I first experienced that the stage can be a space of truth—not only aesthetic or technical truth, but something deeper and profoundly human. Something that goes beyond form and stays with you long after the curtain falls.

The Lesson of the Ensemble

The role of a stage partner is something extraordinary—not just a fellow performer, but a living source of energy, impulses, and meaning. Their presence sets direction, defines rhythm, and opens the space in which I can truly exist as a character. In opera, it’s easy to become enclosed in your own part, your own sound, your own thoughts about how you will be perceived. Theatre taught me that my role only reaches its full dimension in relation to others: when I look, listen, feel, and respond. A partner is both a point of reference and a mirror in which the truth of the moment is reflected. What happens between us matters more than what happens “inside” me—because stage truth is born in dialogue and attentiveness. In those moments, presence becomes complete, and the stage breathes with its own, unrepeatable rhythm.

Technique and the Courage to Let Go

“Love the art in yourself, not yourself in the art.” – Konstantin Stanislavski

In opera, there is a strong temptation—rooted in opera performance tradition—to focus on the brilliance of the sound itself, to dazzle the audience with technical perfection. It’s natural, because technique is the foundation you spend hours refining every day.

Without it, there is no freedom, no safety, no possibility of reaching the full range of expression.

But when the lights go up and the performance begins, there comes a moment when you must trust what you’ve built in the rehearsal room—and let go.

Peter Brook put it simply:

“Hold on tightly, let go lightly.” – Peter Brook

Seize the moment with your whole being, then allow it to pass so the next one can be born. Don’t cling to it; trust that what matters most will happen right here, right now.

This requires balance: alertness and focus to maintain vocal culture and manage energy wisely, so that intensity doesn’t spill over into excess. And at the same time—the willingness to accept that the best moments are born when we stop controlling, when technique becomes a discreet support that allows the moment to unfold naturally.

In that space, vulnerability appears—opening yourself, revealing something intimate, letting the audience in.

The Ethics of Process

At Song of the Goat Theatre—rooted in the tradition of laboratory theatre, whose guiding principles echo those of Stanislavski and Osterwa’s Theatre Reduta, as well as later Polish ensembles like Grotowski’s and Gardzienice—the creative process holds equal weight to the final performance. Rehearsals become a space for free exploration and experimentation, a place to take risks, test ideas, and discover new solutions. It’s in such conditions that truly special moments are born—unrepeatable, authentic, often surprising even to the performers themselves.

Of course, this can’t be directly translated into the working conditions of opera. But the ethic—daily training, attentiveness, respect for your partner and the material—has stayed with me. I know that a performance begins long before the curtain rises. It begins in the work on yourself, in preparing the body and voice, in building trust within the ensemble.

My Philosophy of the Stage

Today, I see the stage as a space for truth. Not realism, but the authenticity of experience. For the audience to believe in what is happening, because I believe in it. The stage is a place of meeting—with yourself, with your partner, with the audience. Every performance is one-of-a-kind, never to be repeated. That’s why presence must be total—undivided, unguarded, and alive to each moment.

In opera, this means that every phrase becomes a vessel for thought and emotion, not merely a showcase of vocal ability. Every sound, every word must come from genuine intention, so that technique becomes a tool for communication, not an end in itself. A gesture, a glance, or a pause gains meaning when it is organically connected to what I want to convey—so that the effect it creates is the natural result of authentic action, not a calculated display.

Legacy and the Future

My approach grows out of traditions I’ve encountered and developed in theatre: Stanislavski’s belief in stage truth, Grotowski’s discipline, the ensemble ethos of Theatre Reduta, Peter Brook’s clarity, and the methodology of Grzegorz Bral, which shapes my understanding of ensemble work and the integration of voice, movement, rhythm, and text.

I don’t believe in final answers. For me, the stage is a place of perpetual beginnings—each time different, each time true only to the here and now. Everything I’ve worked on becomes just a springboard into the unknown. In that risk, in that readiness to step into the dark and allow something to happen, lies the meaning of my work. Because art lives only when it is an act of courage. And this path is never complete—each step teaches me something new, and I will keep learning for as long as I stand on a stage.